9/11: The 911 Call from the West to Africa

In the turn of the 21st century, Africa was regarded as “the hopeless continent”. Africa had lost its strategic position in the post-Cold War environment and became the playground for Western states to exercise their ‘transformative’ ambitions and self-interest, under the veil democracy and good governance. The continent no longer had the power to leverage two superpowers against each other for resources. Capitalism had won. Now, Africa was met with international indifference.

Tuesday 11th September 2001.

The towers fell.

Twelve days later, in his State of the Union Address, George W. Bush uttered the words:

“Our war on terror begins with al Qaeda, but it does not end there”

Marking the subtle, yet important, shift in Africa’s strategic position in the international order.

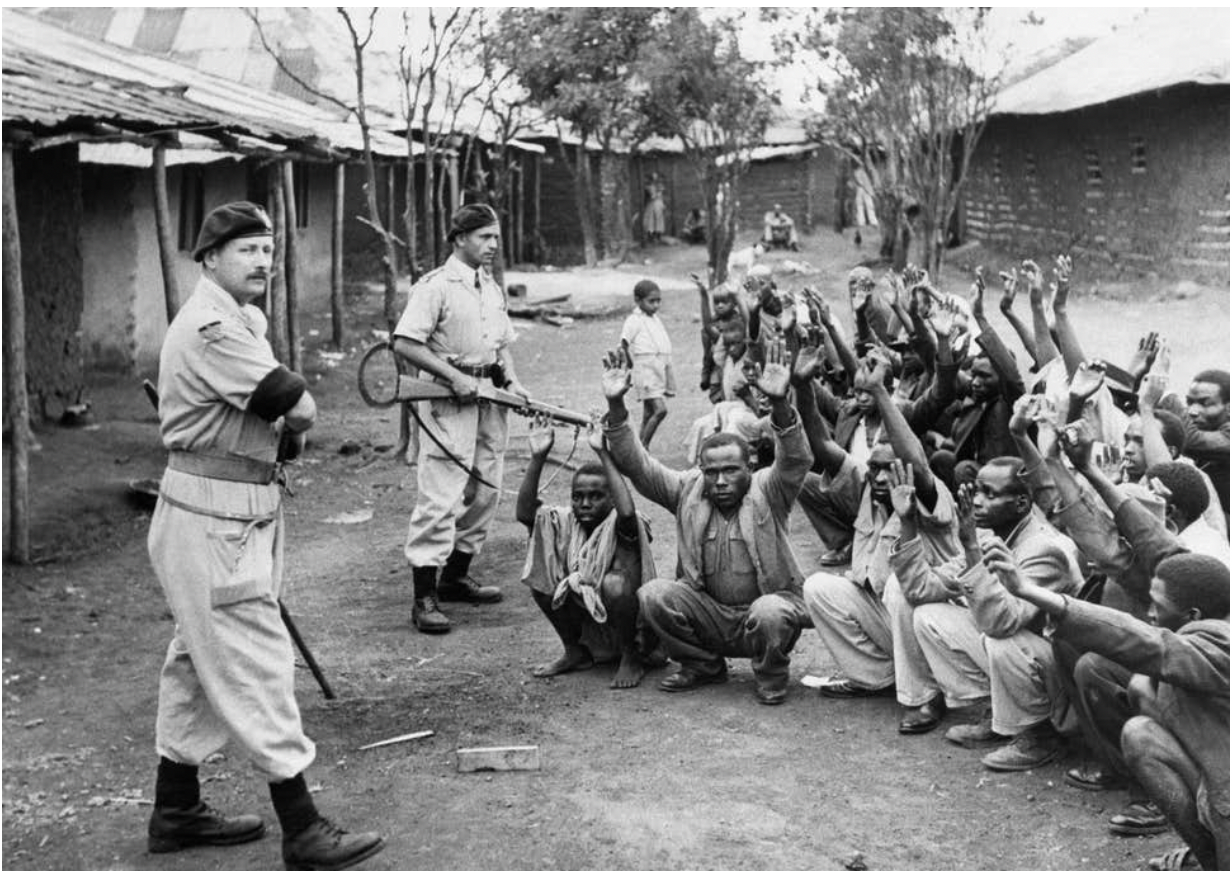

Terrorism in itself did not change the position of African states in the international order — 9/11 did. Terror has long been a feature of African political history. It was used as a para-military tactic that figured in the long anti-colonial struggleand nationalist uprisings across the continent. Not only was it an extension of the anti-colonialism and the fight for freedom but also terror was intrinsic in the institutions of colonialism and slavery.

9/11 demonstrated that fundamentalist and terror groups are capable of launching attacks on Western soil, thereby putting Western lives and interests at risk. So, it was now in the Western interest to halt activities of terrorist groups globally. Prior to 9/11, no sitting Republican president had set foot in Africa but in 2003 Bush visited Nigeria, Senegal, Uganda, Botswana and South Africa. Additionally, during the 2000 presidential electoral campaign Bush proclaimed that impoverished states were not geopolitically significant for the US yet after 9/11 US aid to Africa tripled. This renewed interest in Africa was caused by the belief that poverty can make states vulnerable to terrorism and that the lack of central government reach in the periphery coupled with the porous borders between African states will facilitate movements for terrorist groups.

“Weak states provide both a breeding ground and safe haven for terrorist organisations [and so,] Congress legitimated these claims by creating programmes or funding programmes for a War on Terror in Africa”

Securitisation: the case of post- 9/11 United States Africa Policy byRobin E. Walker & Annette Seegers

Western states rallied to combat the underlying causes of radicalisation and terrorism through aid and military assistance to strengthen the counter-terrorism responses. In 2002, Combined Task 150, a naval unit jointly operated by 25 countries (including, the US, France, UK, Canada and Germany), was deployed to monitor and stop terrorist activity in the Horn of Africa (HOA) and in 2014, France launched OperationBarkhane, to assist Sahelian countries in counterterrorism efforts.

In addition, the creation of the US Africa Command (AFRICOM), a collaborative cross-department military command, to oversee US army, Navy and Airforce activities across Africa, in 2007, concretised the idea that Africa had migrated from the periphery to the core of American security concerns. Even at its peak, Cold War US foreign policy was never this orientated towards Africa. Unlike, Europe and Asia-Pacific, Africa did not have a Command for the whole continent, instead Egypt, the HOA and the Middle East fell under the jurisdiction of the Central Command.

AFRICOM is a very interesting example of renewed Western interest in Africa because it embodies many of the problems associated with Western military presence in the region. Firstly, the Command is riddled with controversy, from excessive drinking to sexual assault and other forms of violence by AFRICOM personnel. Secondly, there is growing concern about the ‘lily pad’ deployment strategy which has resulted in imperial-scale military presence in Africa whilst allowing military commanders to publicly depict all such deployments as ‘temporary’. Thirdly, a journal article by A. Carl LeVan (2010) posited that there is a correlation between government support for AFRICOM, greater aid dependence and slower growth.

French president Emmanuel Macron (L) and his Egyptian counterpart Abdel Fattah al-Sisi at a State Dinner in Cairo (Jan 2019)

Moreover, in light of the rise of the WoT, it appears that many Western donors reverted to their complacent attitudes towards governance failures, that shaped their Cold War foreign policy. For example, despite countless human rights abuses and undermining Egypt’s attempts at democracy, president Abdel Fattah al- Sisi’s regime retains Western support. In fact, Sisi’s regime often utilises WoT rhetoric to justify these actions and the West listens, further perpetrating a cycle of violence and repression. President Emmanuel Macron’s official visit to Egypt in January, truly epitomises the empty rhetoric espoused by Western states. Macron may have publicly urged Sisi's regime to change it's tune regardinghuman rights but if we dig deeper we find that France became Egypt’s top supplier of arms supplierof arms in recent years.

To conclude, discussions of 9/11 that go beyond analyses of US-Middle East relations are necessary when trying to navigate and understand the full picture of 9/11’s geopolitical consequences. The increased focus on Africa post-9/11 truly exemplifies the blurred lines that exist between Western intervention for humanitarian reasons and interventions based on self-interest. Lastly, it is important to note that. the emphasis placed on the promotion of security draws attention away from Western contribution to the problems of underdevelopment and state failure, through military presence and aid strengthening repressive regimes.